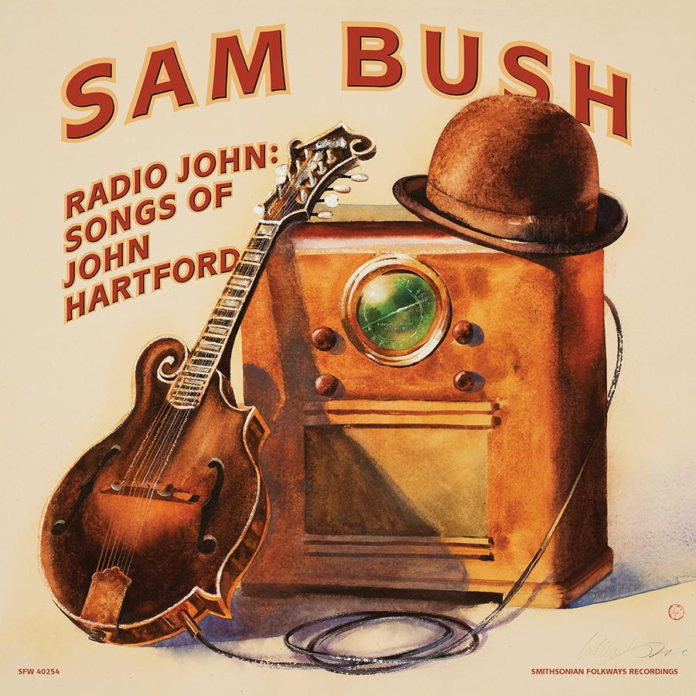

Available for preorder now for Digital, CD, and Vinyl: https://folkways.si.edu/sam-bush/radio-john-songs-of-john-hartford

On November 11, International Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame member Sam Bush will pay tribute to his longtime friend and collaborator John Hartford on Radio John: Songs of John Hartford. Bush’s first album since 2016, Radio John is his heartfelt tribute to his hero and mentor, digging deep into the American roots music eccentric’s vast catalog to pull out personal favorite songs, including some he played with Hartford himself in the 1970s. Bush plays every instrument—acoustic guitar, mandolin, banjo, electric bass, fiddle—on every cut except the big, full band finale “Radio John,” the collection’s one original song and a tribute to Hartford that Bush wrote with John Pennell.

In the liner notes, Bush recalls a lifetime of Hartford fandom starting the day he heard Hartford playing three-finger banjo on The Wilburn Brothers Show on a Saturday afternoon in 1967. He first saw him in concert two years later, in Bush’s hometown of Bowling Green, Kentucky: “I was in the high school marching band my senior year. We did our rainy football halftime performance and I hightailed it to E.A. Diddle Arena in my muddy band uniform in time for his show.” Within just a few years, Bush’s new band New Grass Revival was opening up for Hartford and often joining him onstage performing the songs off Hartford’s pioneering 1971 album Aereo-Plain. The jam sessions continued until Hartford’s passing in 2001.

Today, Hartford’s best-known song is probably “Gentle on My Mind,” made a hit by Glen Campbell in 1967. But as Bush demonstrates on Radio John, Hartford’s catalog goes far deeper. The early success of “Gentle on My Mind” freed Hartford from a need to concern himself with the quotidian preoccupations of a performer—or a songwriter—just trying to keep a roof over his head and a biscuit on the table. So he meandered through the 1970s and ’80s, scattering musical and non-musical nuggets everywhere he went: consider the startlingly creative fusion of 1971’s Aereo-Plain or the solo-performance run that began with 1976’s Mark Twang, which won the GRAMMY award for Best Ethnic or Traditional Folk Recording—though it could be seen as traditional only through an act of imagination. By 1990, his precisely modulated drawl had become such a rich, expressive vehicle that documentary filmmaker Ken Burns drew on it for narration in his Civil War series. A decade later, Hartford helped spearhead the early 21st-century eruption of roots music into the mass consciousness, exemplified by 2000’s O Brother, Where Art Thou?, which featured several of his songs and was released shortly before he died.

Like Hartford, Bush is liable to turn up almost anywhere. A pioneer in the ʼ70s and ʼ80s progressive bluegrass movement sometimes termed “newgrass,” he recorded with icons including Doc Watson and Emmylou Harris and younger stars like Garth Brooks and Shania Twain. He won a Lifetime Achievement Award for Instrumentalist from the Americana Music Association in 2009 and was inducted into the International Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame in 2020. In 2010, Kentucky officially named his hometown of Bowling Green the “Birthplace of Newgrass” and him the “Father of Newgrass.”

Bush first conceived of the album on a pre-pandemic trip with his wife to the Florida panhandle. He had brought an array of instruments and began playing around with songs from the vast Hartford catalog. He intended to record demos for his band, but, as he jokes, “in true Sam style, lack of engineering skills and patience, I was having a rough time overdubbing by myself.” When he mentioned his lack of home recording skills to a friend, Donnie Sundal, co-owner of Neptone Recording Studio in Destin, Florida, Sundal soon showed up at their beach carriage house dragging along all the equipment for a professional session. “In no time, we were laying down tracks (and he engineered),” Bush writes. “Only then did I realize this could be a true solo endeavor of my love affair with John Hartford’s music.” When the pandemic hit, he gave those recordings a final polish with sound engineer Rick Wheeler.

In his song selections, Bush focuses not on Hartford the curator and impresario of fiddle tunes, but rather on Hartford the singer-songwriter, who came to Nashville as a colleague of writers such as Kris Kristofferson and Tom T. Hall, shaking up Music Row with distinctive songs that channeled the growing tides of the counterculture into their publishing houses and studios. To do so, he digs beyond than “Gentle on My Mind” to mine songs of heartbreak (“A Simple Thing as Love”) and humor (“Granny Wontcha Smoke Some Marijuana”). Many of the songs Bush had played on with Hartford originally, and in the liner notes he shares memories of listening with him to the Mahavishnu Orchestra (“John McLaughlin”) and helping him rerecord songs he had first related to as a kid growing up on a farm (“In Tall Buildings”).

Radio John is a testament to the impact Hartford had on American traditional music as a songwriter, an instrumentalist, and, most importantly, someone who fostered the careers of musicians like Bush and countless others reinventing roots music in the last half of the 20th century. More simply, Bush calls it “my love letter to John Hartford’s music that I hold so dear.”