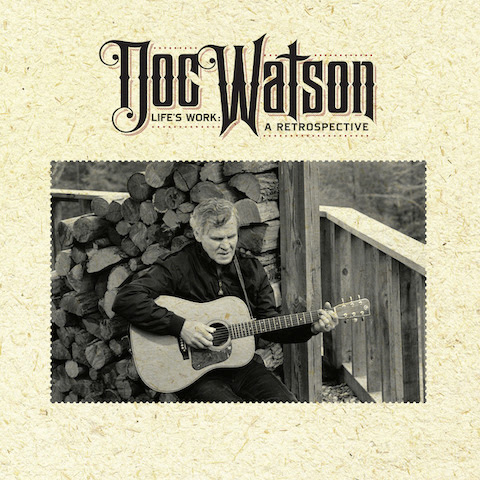

Life’s Work: A Retrospective—a new, career-spanning collection that celebrates the life, music, and enduring influence of the iconic guitar virtuoso Doc Watson, is out from Craft Recordings; listen/buy here. Available today at DSPs, the 4-CD box set will follow on December 3, and exclusive bundles are available only on the Craft Recordings webstore.

Life’s Work: A Retrospective is garnering critical acclaim:

“…this is the set Watson’s innumerable fans have longed for.” –The Wall Street Journal

“The box set is a must for any Doc Watson fan…”—Garden & Gun

“Watson brought his music down from the mountains to share with the world, and as this collection ably demonstrates, the world is better for it.” –No Depression

“Life’s Work amply demonstrates why Watson’s fretwork on both the banjo and guitar propelled him to iconic status.”—Holler

The box set includes 101 tracks from the legendary roots artist, including collaborations with Alison Krauss, Chet Atkins, Bill Monroe and Ricky Skaggs. The collection also features Watson’s work with the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, as well as his prolific musical partnership with his son, Merle. Accompanying the 4-CD set is an 88-page book, featuring extensive new liner notes by GRAMMY®-nominated author and compilation co-producer Ted Olson, plus never-before-seen photos.

Born and raised in Deep Gap, North Carolina, Arthel Lane “Doc” Watson (1923–2012) was born into an extended family of musicians who were masters of the traditional ballads, fiddle tunes and hymns of Appalachia. Watson, who lost his vision as a toddler, began playing the guitar as a child, earning the nickname “Doc” at a local talent competition. In his 30s, he gained valuable experience in a country dance band, often performing the fast-paced, lead fiddle parts on guitar—a signature technique that he brought to his solo work. His incomparable fingerpicking and flat-picking skills influenced generations of artists, while his wide-open ears led him to incorporate jazz, blues, country and pop music influences—a sensibility that coalesced into what he called “traditional plus.” He was also renowned for his harmonica and banjo playing, and his soulful baritone voice (especially on an a cappella ballad such as “Talk About Suffering”).

In his liner notes, Olson speaks to Watson’s unique approach to the guitar: “His facility with melody and rhythm and his daredevil improvisations with flat-picking fiddle tunes…drew a large, enthusiastic, and informed fan base.” He adds that Watson’s “resonant and pitch-perfect vocals, his extensive repertoire of traditional and commercial music, and his comforting and lively stage presence [made him] a complete performer [who] proved himself proficient as the proverbial one-man-band.”

Despite his talents, however, Watson didn’t gain wide acclaim until his 40s, following several pivotal events. The first was a genre-defining folk concert at Greenwich Village’s P.S. 41, followed by a pair of awe-inspiring performances at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival. A year later, he released his solo debut. The self-titled album was released on Vanguard Records, a New York-based label with Classical roots which at the time was emerging as a force in folk music, its roster including Joan Baez, The Rooftop Singers and Buffy Sainte-Marie. The album found Watson interpreting a variety of folk, country and blues songs—many of which would become standards for the artist—including the Dorsey Dixon/Wade Mainer tune “Intoxicated Rat,” Dock Boggs’ “Country Blues” and the traditional “Black Mountain Rag.” Watson would go on to release several classic albums with Vanguard in the beginning of his career, which would help to establish him as one of the most influential folk artists of his time.

These early years of fame found Watson inspiring a wide range of artists, including Baez, Jerry Garcia, Ry Cooder, Stephen Stills and Peter, Paul and Mary. But that admiration went both ways. As Olson points out, “Doc understood he had much to learn from younger people whose backgrounds were different from his own.” Watson, in turn, often covered songs by popular folk artists, including Bob Dylan and Tom Paxton.

Although the folk revival began to wane by the end of the ’60s, Watson found a new fanbase through his participation on the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s 1972 album Will the Circle Be Unbroken. The highly influential title paired the country rockers with an older generation of bluegrass and country artists, including Earl Scruggs, Roy Acuff, Maybelle Carter and Merle Travis. Watson’s rendition of Jimmy Driftwood’s “Tennessee Stud” became a breakout hit, while the album, Olson writes, “proved a watershed event in [Watson’s] career, expanding his audience from his core fan base (holdovers from the urban folk music revival as well as already-initiated fans from the country and bluegrass camps) to encompass many new fans from the early 1970s counterculture.”

Watson’s career cannot be summed up without the mention of his son and longtime collaborator, Merle. Born Eddy Merle Watson (and named for Merle Travis), the younger artist not only shared his father’s uncanny talents on the guitar but was also integral in helping Doc build a wider following. The duo—who later performed in a trio setting with bassist T. Michael Coleman—began their musical partnership when Merle was just a teenager and went on to record more than a dozen albums together, including Doc Watson & Son (1965) and Ballads from Deep Gap (1967) as well as the GRAMMY®-winning titles Then and Now(1973) and Two Days in November (1974). “Merle’s musicianship perfectly complemented Doc’s,” writes Olson. “Proving to be an exceptionally gifted musician, Merle would contribute rhythmically solid and fluid guitar and banjo accompaniment to nearly two decades of Doc Watson performances and to many of Doc’s most memorable recordings.”

Tragically, their incredible run ended in 1985 when a 36-year-old Merle lost his life in a tractor accident. Watson honored his son’s memory by founding MerleFest, a music festival in Wilkesboro, North Carolina, that brings both traditional and contemporary roots artists to the stage (the blend that the Watsons would refer to as “traditional plus”). Today, more than 30 years later, the annual event attracts roughly 75,000 fans from around the world.

In his later years, Watson continued the family musical tradition by touring with Merle’s son, Richard, with whom he recorded the GRAMMY®-nominated album Third Generation Blues. Watson also enjoyed working with a new generation of artists and fans, including Bluegrass Hall of Fame inductee Tony Rice, multiple GRAMMY®-winner Allison Kraus and the best-selling Americana trio Nickel Creek.

While Watson died in 2012 at the age of 89, he lived to see the incredible impact of his work. Among his many honors, he received the National Heritage Fellowship in 1988 from the National Endowment for the Arts—the highest honor that a folk artist can receive from the US Government. Nearly a decade later, Watson was presented with the National Medal of Arts by President Bill Clinton. In 2000, he was inducted into the International Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame, while throughout his five-decade-long career, the artist earned eight GRAMMY® Awards, including a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2004.